“企鹅经典”英译本Rutherford导论之一 - 《堂吉诃德》的写作(上半部分)(惩恶扬善故事集是谁写的)惩恶扬善故事集,

Don Quixote在“Penguin Classics(企鹅经典系列,据说里面收了1100多本著作)”里收录的英译本是由John Rutherford翻译的。

我看了个开头,觉得文笔极好,很有那个味(characteristic iconic self-mockery,典范性的自嘲)。我不会西班牙文,当然没办法像评价《不起的盖茨比》汉译本或者许渊冲古诗英译那样直接去评价翻译。但是我觉得其他几个译本可能过于强调文本直译和意思的还原,丢失了或者减损了一些俏皮的自嘲意味。当然本导论中Rutherford有对几个英译本的点评,敬请期待。

插句话,同时期中国类似的名著应该是《西游记》,大概是明万历年间1580年代成书的,比《堂吉诃德》就早个几十年而已,也有着杰出的讽世精神。据王水照老先生的《钱锺书的学术人生》一书说钱老先生就特别喜欢看《西游记》,一生中翻阅十数遍。还有人说《围城》就受了《西游记》的影响。

1600年代在西方正是漫长的千年中世纪(500~1500)的结束,西方世界迅速进入文艺复兴之后波澜壮阔大航海,大发现,大殖民移民以及科学技术大发展的时代。思想上迅速解放,见识上迅速扩展。这样的时代必将产生卓越的精神产品(塞万提斯和莎士比亚在欧洲一南一北几乎同时出现)。

塞万提斯(1547~1616)

1569年(22岁)跟随枢机主教访问罗马。23岁开始从军,24岁(1571年)参加了整个基督教世界联军对抗奥斯曼帝国的勒班陀海战,左手因战斗残疾。25~28岁转战于西班牙东海岸,希腊,意大利等地。1575年回西班牙途中被海盗俘虏,送到阿尔及尔囚禁。1575~1580(28~33岁)在阿尔及尔当俘虏期间数次向西班牙几位大臣写信求助,并且创作了一些幕间短剧和喜剧。后被家人用五百金盾赎回。《唐·吉诃德》中的俘虏经历就是塞万提斯这段生活的写照。1581~1582年在里斯本结识了葡萄牙的安娜·弗兰卡夫人,并养有一女伊萨贝尔·德萨阿韦德拉。1583年由于手头拮据,及其左手残废而无晋升机会,被迫离开军队。1584年(37岁)同西班牙的卡塔利娜·德帕拉西奥斯·萨拉萨尔结婚。1585年出版了《加拉特亚》第一部,随后出版了《阿尔及尔生涯》和《努曼西亚》。1587~1589年在安达卢西亚接受了皇家军需官的职务,负责为无敌舰队和陆军采购军需品。1590年向国王请求到西印度群岛供职,未获准。1591~1592年辗转于村落之间采购军需品,后被诬告为帐目不清,身陷囹圄。1594年回到马德里,后任格拉纳达税史。1597(50岁)年被人指控为私吞钱财,再次入狱,三个月左右蒙恩获释。期间,官差丢失,为了糊口度日,他为别人跑腿,拉纤,沿街叫卖布匹。这段不幸的遭遇加深了他对人民的同情和贵族僧侣的憎恨。这一点,在他后来的作品中得到了异常鲜明的反映。1598年获释出狱,担任一些私职,其间创作了一些诗歌、十四行诗和一首歌谣。1603年赴巴利阿多里德为自己洗刷冤名,随身携《唐·吉诃德》上卷手稿。1605年《唐·吉诃德》上卷出版,一年之内再版六次。不料又卷入一场官司中,同姐妹、女儿和外甥女一起在牢房中度过了几天。事实澄清后获释。1606年在马德里落脚,担任私职,经济状况窘迫。《唐·吉诃德》被译成欧洲几种主要语言。1609年加入圣体教友会。1613年加入圣方济会,《惩恶扬善故事集》出版。1614年《帕尔纳索游记》出版。1615年《八部喜剧及八部幕间短剧集》和《唐·吉诃德》下卷出版。1616年身患严重水肿,患病期间仍然对生活充满了乐观精神。此间,他为他的小说《佩西莱斯和塞西斯蒙达》写了《向莱穆斯伯爵致辞》,五天后,即4月23日逝世于马德里。他死后,被草草安葬在一家修道院的墓地,参加他葬礼的除了他妻子,什么人也没有。直到他逝世两百多年以后,即一八三五年,马德里才为这位西班牙人衷心爱戴的作家建立了一座纪念碑。堂吉诃德和侍从桑丘的雕像也高高地立在马德里广场上。

1569年(22岁)跟随枢机主教访问罗马。23岁开始从军,24岁(1571年)参加了整个基督教世界联军对抗奥斯曼帝国的勒班陀海战,左手因战斗残疾。25~28岁转战于西班牙东海岸,希腊,意大利等地。1575年回西班牙途中被海盗俘虏,送到阿尔及尔囚禁。1575~1580(28~33岁)在阿尔及尔当俘虏期间数次向西班牙几位大臣写信求助,并且创作了一些幕间短剧和喜剧。后被家人用五百金盾赎回。《唐·吉诃德》中的俘虏经历就是塞万提斯这段生活的写照。1581~1582年在里斯本结识了葡萄牙的安娜·弗兰卡夫人,并养有一女伊萨贝尔·德萨阿韦德拉。1583年由于手头拮据,及其左手残废而无晋升机会,被迫离开军队。1584年(37岁)同西班牙的卡塔利娜·德帕拉西奥斯·萨拉萨尔结婚。1585年出版了《加拉特亚》第一部,随后出版了《阿尔及尔生涯》和《努曼西亚》。1587~1589年在安达卢西亚接受了皇家军需官的职务,负责为无敌舰队和陆军采购军需品。1590年向国王请求到西印度群岛供职,未获准。1591~1592年辗转于村落之间采购军需品,后被诬告为帐目不清,身陷囹圄。1594年回到马德里,后任格拉纳达税史。1597(50岁)年被人指控为私吞钱财,再次入狱,三个月左右蒙恩获释。期间,官差丢失,为了糊口度日,他为别人跑腿,拉纤,沿街叫卖布匹。这段不幸的遭遇加深了他对人民的同情和贵族僧侣的憎恨。这一点,在他后来的作品中得到了异常鲜明的反映。1598年获释出狱,担任一些私职,其间创作了一些诗歌、十四行诗和一首歌谣。1603年赴巴利阿多里德为自己洗刷冤名,随身携《唐·吉诃德》上卷手稿。1605年《唐·吉诃德》上卷出版,一年之内再版六次。不料又卷入一场官司中,同姐妹、女儿和外甥女一起在牢房中度过了几天。事实澄清后获释。1606年在马德里落脚,担任私职,经济状况窘迫。《唐·吉诃德》被译成欧洲几种主要语言。1609年加入圣体教友会。1613年加入圣方济会,《惩恶扬善故事集》出版。1614年《帕尔纳索游记》出版。1615年《八部喜剧及八部幕间短剧集》和《唐·吉诃德》下卷出版。1616年身患严重水肿,患病期间仍然对生活充满了乐观精神。此间,他为他的小说《佩西莱斯和塞西斯蒙达》写了《向莱穆斯伯爵致辞》,五天后,即4月23日逝世于马德里。他死后,被草草安葬在一家修道院的墓地,参加他葬礼的除了他妻子,什么人也没有。直到他逝世两百多年以后,即一八三五年,马德里才为这位西班牙人衷心爱戴的作家建立了一座纪念碑。堂吉诃德和侍从桑丘的雕像也高高地立在马德里广场上。以上抄自百度百科。这种波澜壮阔的人生阅历可能只有先秦诸子,汉晋唐代诸贤,宋之苏辛可以比肩吧。

回到《堂吉诃德》企鹅英译本,译者Rutherford写了很长的一篇导论Introduction,分为两部分,分别是:

Writing Don Quixote,讲他怎么认为塞万提斯是如何写作《堂吉诃德》这本杰作的。Translating Don Quixote,讲他怎么翻译这本书,讲他的一些翻译理论和实践,以及对其他英译本的点评。我读过一遍之后,觉得这个导论很有意义,不妨做一个精读,既加深自己的理解,也和大家共享一下。看看英语界的翻译大师是怎么来看待翻译以及怎么看这本小说的。原文有点长,所以我按原文本来就有的writing/translating两部分分成两篇精读(可能需要进一步分成四篇,因为实在太长了)。

顺便说一下,企鹅现代经典系列(好像偏重于收20世纪以后的经典著作)里The Great Gatsby的导论也非常赞,以后也找有机会精读一下。

Introduction

WRITING DON QUIXOTE

‘I do now have to say,’ said Don Quixote, ‘that the author of my history was no sage but some ignorant prattler, who started writing it in a haphazard and unplanned way and let it turn out however it would, like Orbaneja, the famous artist of Úbeda, who, when asked what he was painting, replied: “Whatever emerges.” ’

(Don Quixote, Part II, chapter III)

Rutherford在writing/translating两部分的开头都引用了一段小说Don Quixote的原文作为引子。sage, 圣人。prattle,小孩牙牙学语,成人闲聊胡扯。haphazard, 偶然,随意的random。和unplanned近义词。Whatever emerges,有点spontaneous,自发的,随意的意思。和上面的haphazard和unplanned意思相近。英语里面的synonym真是让人发指的多。Rutherford引用本段的意思应该是说Cervantes写这本书并没有特别强的规划性,有点自发涌现野蛮生长的意思。也许这样的写作才能诞生真正的杰作吧,就像文思天然泉涌,无需太多人工雕琢。后面会有详细阐释,往后看。这一小节里面内容原文是一个自然段,过长,我把它分成了三段方便阅读。后面体例同,不再另外解释。

In the Prologue to Part I, Cervantes tells us that it was while he was in prison that he had the idea for Don Quixote. It’s probable that he’s referring to his incarceration in Seville (1597–8), for incompetence as a tax-collector. Nobody knows whether he started writing while in prison, or later. But what is clear is that the piece he envisaged was very different from what he was eventually to produce.

incarceration, 监禁,就是put in prison的意思。塞万提斯坐牢的原因文章里说是incompetence as a tax-collector(税吏不胜任),据百度塞万提斯词条说是担任税吏(1594~1597)被人指控(不知道是不是诬告)私吞钱财而入狱,三个月后蒙恩释放。本小段是说在小说第一部分的开场白(Prologue)里塞万提斯说自己是在某次坐牢的时候有了《堂吉诃德》一书的构思的。Rutherford说应该是1597年这次坐牢。根据百度词条1592年时塞万提斯在西班牙无敌舰队军需官任上也坐过一次牢,但那时候离上册出版(1605年)有点久远了。税吏和军需官都是肥差,自然有人觊觎告黑状。塞万提斯在1605年出书那年还坐了一次牢,一辈子也算是三进三出,三起三伏了。envisage, 设想。Rutherford认为即使真的是1597年就有了某种构思,那个构思也肯定是和后面实际写成的书非常不同的。Cervantes was thinking of a short fiction, something along the lines of his Novelas ejemplares, or exemplary novellas, eventually published in 1613. This is indicated by the rapid pace and short duration of the knight’s first sally, undertaken alone and occupying just the first five chapters, and by the fact that in the seventh sentence of the text the narrator refers to it as a cuento, a short tale, something he does only once more (see below): as soon as the fiction is fully under way Cervantes calls his text a libro (book) and an historia (history or story), reserving cuento for the tales contained within it.

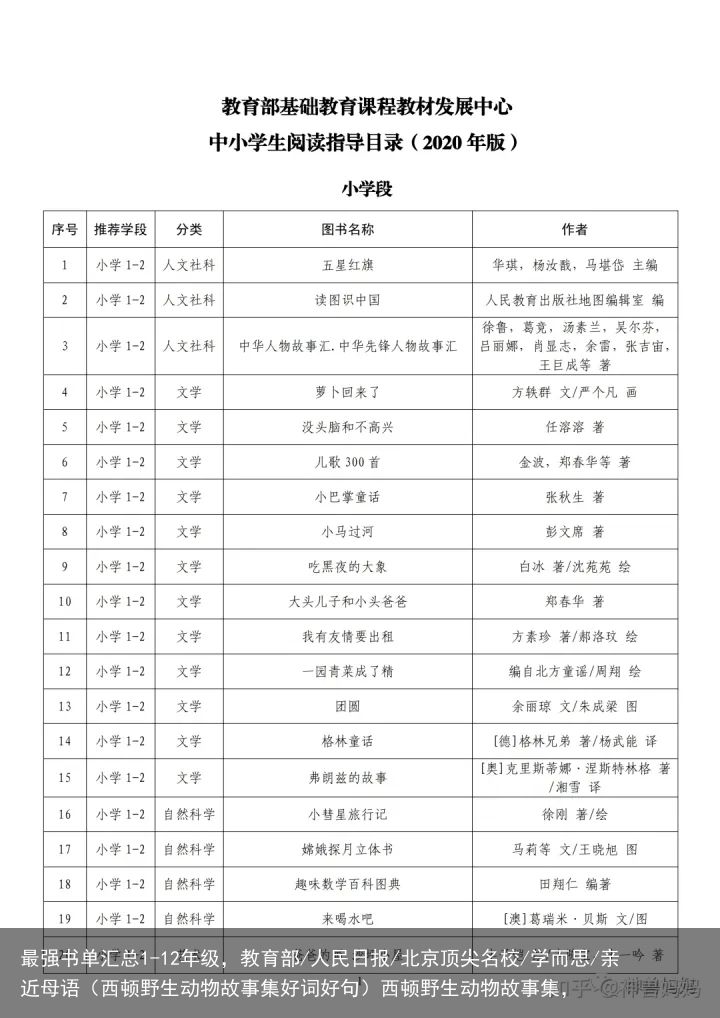

塞万提斯一开始构想的是短篇小说(short fiction/novella),也就是类似他在1613年出版的《惩恶扬善故事集》那样的短篇小说合集里的东西。sally,出击,突击,就是堂吉诃德某次冒险,比如向风车“巨人”冲锋那个就是一次sally。风车冒险是《堂吉诃德》中第二次出击(和随从桑丘合作的第一次),在这个之前有一次堂吉诃德独自出发的冒险,占了全书前五章。这部分写得节奏很快,持续很短,表明了塞万提斯一开始的创作思路。还有个实证是在这次突击的第七句话narrator(本书写作特色,会有故事讲述人出现,有点类似《红楼梦》开头提到的为石头作传的情僧。但不同的是讲述人有多个,而且互相观点打架,不像我们这里认为只能有一个观点才是正确的)自称为a short tale。后来随着小说的持续展开,塞万提斯开始自称为book或者history,而把short tale专用于书中提到的某些小故事了。But by the time he reached the end of the first sally, he’d begun to realize that he must explore this fascinating fictional world he’d stumbled upon. So what perhaps started as a more or less moral fable, using parody to attack romances of chivalry for their pernicious effects on readers, turned itself, as it was being written, into the first modern novel. In his anecdote about Orbaneja, Cervantes tells us, with characteristic ironical self-mockery, how he created his great work.

写到第一次冒险尾声时,塞万提斯开始意识到他必须好好探索拓展(explore)一下他创造的这个神奇虚拟世界。他一开始策划的本来只是一个道德寓言(fable),一个故意模仿(parody)骑士小说的滑稽戏,以嘲讽当时那些骑士小说不切实际的浪漫以及这些东西对读者的毒害(pernicious effects),到最后他的著作却变成了第一本现代意义的小说(modern novel)。在导论开头引用的那段关于Orbaneja的轶事趣闻(anecdote)里,塞万提斯其实以他标志性的自嘲形式向我们透露了他是怎么创造了他的杰作的(Whatever emerges,并没有预先规划的,自然涌现的,写出来啥就是啥)。Yet the moralizing content of even the first conception of Don Quixote is dubious. Its hero is as obsessed by the traditional Spanish ballads and their protagonists as by the romances of chivalry: stories about enamoured knights in shining armour wandering through exotic lands slaying giants and the occasional dragon and rescuing damsels in distress in order to prove their prowess as fighters and their perfection as lovers, despite all the worst efforts of evil enchanters. The romances of chivalry had enjoyed great popularity and had been attacked by moralists for turning readers’ thoughts, in particular young female readers’ thoughts, away from religion towards worldly matters.

conception, 构思。dubious,可疑的。然而,即使是《堂吉诃德》最初的构想,它的教化内容也是可疑的。它的英雄(吉诃德老爷)既迷醉于传统的西班牙民谣(ballad)和里面的主角,也迷醉于骑士精神(chivalry)的浪漫:心中爱意燃烧(enamored)、满身亮闪盔甲的骑士在奇异(exotic)之地冒险,杀死巨人或者恶龙,拯救绝境中的少女,以证明他们作为战士的技艺,作为爱人的完美,蔑视所有邪恶巫师的邪恶企图。这种骑士浪漫故事(romances of chivalry)曾经非常流行,而且一直都被道学家(moralist)们攻击,说它们荼害了读者 - 特别是年轻女性读者 - 的心灵,让她们不再信仰宗教而转向俗世凡尘(咋跟《西厢记》一回事)。But all this had happened in the first seventy years of the sixteenth century. Since then the romances of chivalry had been superseded by the flowering of literature that we know as the Spanish Golden Age, and by Cervantes’s time nobody considered them to be a threat any more. The theatre was the new literary moral menace. Yet at a time when, following the classical dictum, fictional literature was supposed not only to delight but also to instruct, and when the authorities could censor and ban books, it was wise to claim some orthodox moral purpose for what one wrote, particularly if its irreverent irony could suggest critical thoughts about certain aspects of Roman Catholic practice such as the trial and burning of heretics, the use of rosaries and the repetition of Hail Marys and creeds.

但是这些骑士浪漫小说的流行是16世纪前70年的事情。随后西班牙文学黄金时期开始了,到塞万提斯的时候已经没有人认为骑士小说是个值得一提的对道德教化的威胁了,戏剧是人们新的担忧(又让人想起了《西厢记》)。在那个时代,大家都公认(classical dictum)文学作品不仅为了娱乐(delight)大众,也应该有教化(instruct)作用(其实现在也一样吧)。因此明智的做法是为书中内容宣称某些正统道德教化,特别是当书里一些佯狂不经的嘲讽(irreverent irony)段落可能会让人觉得它们是对罗马天主实践的批评,这些实践包括对异教徒的审判和火刑,念玫瑰经和重复喊“圣母玛丽亚”和教义等等。玫瑰经 [rosary]

宗教仪式。即一边背诵祈祷文,一边数珠串或打节的绳索,这些念珠和绳索也被称为玫瑰经。这类器件大多都具有很强的装饰性,且镶有宝石。使用玫瑰经或“念珠”的做法在世界上各宗教中流传甚广,包括基督教、印度教、佛教以及伊斯兰教。在基督教中,最普遍的玫瑰经是圣母马利亚的玫瑰经。起源不详,但与圣多明我有关,并在15世纪形成确定形式。But the evidence indicates that the delight interested Cervantes more than the instruction. What he relished was the joy of storytelling, the fun of parody, humour as something good in itself because of its therapeutic value. His allegation of an unconvincing and anachronistic moral purpose is perhaps part of the fun, yet another parody. And the joke is still funny today, because the book that claims to destroy romances of chivalry is the one that has kept their memory alive.

但是很显然塞万提斯更感兴趣的是让读者欢笑,而不是对读者说教。《堂吉诃德》一书充满了(relish)讲故事的欢乐,拙劣模仿的搞笑,某些事情本身的滑稽和幽默以及它的治愈性价值。塞万提斯为了自保,也对教化主题进行了自我宣称,但他的宣称显然不能让人信服而且也是内容过时的(anachronistic),这种半心半意的教化宣称本身就是小说笑料的一部分,也是另一种故意的模仿搞笑。这种玩笑到今天仍然好笑,因为这本书宣称是要摧毁骑士传奇小说,但恰恰是这本书把骑士传奇最鲜明的保留在人类的文学记忆里面。To read this lovely novel is to accompany its author in an exhilarating adventure as he improvises his story and watches it grow between his hands. It is also to understand that it would be mistaken to expect it to be a tightly structured book. Despite the best efforts of academic critics, Don Quixote is an episodic work, as also are the romances of chivalry, consisting as they do of successions of chance encounters.

exhilarating, 让人愉快的。improvise,即兴创作。欣赏这本可爱的小说最好的办法就是,和它的作者一同踏上让人愉悦的冒险,看作者如何即兴展开他的故事,看它怎么生长。如果期待这本书是一部结构谨严的作品,那绝对就是个错误。episodic,插话式的。《堂吉诃德》是一部大杂烩式(episodic)的作品,骑士小说也是如此,由一连串的随机遭遇冒险拼凑而成。The first development after that brief first sally is to provide Don Quixote with a squire, Sancho Panza, which opens the way to the conversations that alternate with the action. The possibility of enlisting a squire had been suggested, but not put into practice, during the first sally. Long conversations between knight and squire are not a feature of the romances of chivalry, yet their contribution to Don Quixote is vital, allowing this novel of comic adventures to become a comedy of character as well.

小说在吉诃德老爷第一次独自冒险结束之后,给他加了个侍从桑丘。这样就在行动之外引入了会话。骑士和侍从直接的长篇对话并不是骑士传奇小说的特点,但这个对《堂吉诃德》一书却是至关重要的。小说因此从冒险喜剧进化成了性格喜剧。Quixote and Sancho first appear as two-dimensional figures of burlesque fun, both derived from recent Spanish literature: Quixote is an aging madman who thinks he’s a knight errant and brings amusing disasters upon himself; and Sancho is the rustic buffoon, selfish and materialistic, who was a stock character in sixteenth-century Spanish comedies. Both are absurdly unsuited for their roles: in the romances of chivalry, knights and squires are young men of high birth, with the latter serving their apprenticeship before becoming knights themselves.

吉诃德和桑丘最初都是一种模仿滑稽戏的二维(平面)角色,来自于对当时西班牙文学的模仿:吉诃德是一个疯老头子,自认为是个骑士游侠(knight-errant),给自己带来滑稽搞笑的灾难;桑丘是个村夫小丑,自私,物欲横流,这是16世纪西班牙喜剧的常见(stock)角色。两个人物都并不是模仿对象的典型形象。在骑士传奇里面,骑士和侍从都是高贵血统的年轻人。侍从只不过是更年轻一些,暂时作为学徒服务于骑士以积累经验,以将来自己成长为骑士。But these two clowns soon start to develop, as does the relationship between them. Each begins to show contradictory characteristics: Don Quixote is allowed his lucid intervals, derived from contemporary medical theories about the nature of madness, and Sancho acquires cunning and a certain sagacity, from the peasant figure in folk tales. They both gain depth and complexity – a sane madman and a wise fool – and the humour becomes more subtle, although burlesque is never abandoned. Above all, both Quixote and Sancho acquire the ability to astonish us, always however in convincing ways.

lucid, 头脑清楚的。cunning, 狡猾。sagacity,睿智,明断。两个小丑(clown)样的角色都开始发展,他们彼此间的关系也开始发展。有发展的角色才显得真实。中国几大名著里的角色往往就缺少这种发展性。每个角色都开始呈现性格的对立面(变得立体了)。堂吉诃德会在疯癫的间隙里变得头脑清楚,这个和现代精神病人的医学理论相合;桑丘获得了狡猾聪慧,类似民间传说里的农民角色。因此两个角色都拥有了深度和复杂性 - 一个明智的疯汉和一个聪明的笨蛋。因此全书的幽默性开始变得微妙深刻。两个角色都能让我们惊奇(astonishing)而不仅仅是逗乐了。Here two principles of Golden Age literary theory are relevant: the belief that admiratio (amazement) and verisimilitude are essential qualities of fictional literature underlies our two heroes’ wonderful combination of unpredictability and credibility. Don Quixote is an experimental work far ahead of its times, yet it is also rooted in its times. Its protagonist’s determination to turn his life into a work of art, which will reach its climax in his penance in the Sierra Morena, is the consequence of the crazy application of yet another Renaissance literary principle, that of imitatio, the importance of the imitation of literary models.

amazement, 惊奇。verisimilitude,逼真。既让人惊奇但又让人觉得真实,这是西班牙黄金文学时期对好的文学作品的两个准绳。书中两位英雄完美结合了不可预测性(惊奇)和可信度(逼真)。《堂吉诃德》是一个远超于它的时代的先驱试验性作品,但也深植于它的时代。书的主角决心把自己的生活变成一场艺术,在他于Sierra Morena苦修(penance)时达到高潮,是另一个文艺复兴文学原则让人惊异的应用的结果。这个原则就是模仿(imitatio),对文学典范作品的模仿的重要性。Cervantes was particularly proud of having created Sancho Panza, to judge from what he says at the end of the prologue. And as soon as Sancho has appeared, Cervantes relates what will become the most famous incident in the book, the adventure of the windmills. Readers wonder why it’s narrated so briefly, but the reason is clear enough: the story has only just started to expand, it hasn’t yet grown from a cuento into an historia. Readers might also wonder why it has become the most famous episode: simply because it’s the first adventure that knight and squire have together?

塞万提斯对创作出桑丘这个角色很自得,他在序曲末尾说的话表明了这一点。堂吉诃德和桑丘两人合作的第一次冒险就是全书最有名的一次:风车冒险。读者可能会吃惊为什么这次冒险如此简短?因为全书还在扩展,还没有从塞万提斯一开始策划的小故事合集变成一部长篇历史小说。读者也可能会问为什么这次冒险会如此有名?也许只是因为它是两人合作的第一次吧。The second stage in this spontaneous development into a novel is the invention of the narrators. Throughout the first sally the story has been told by an unnamed narrator to whom no particular importance has been attached. Here again, however, there are hints of what’s to come as we’re informed of differences of opinion on factual matters among the various authors who have written about Don Quixote, and as he himself anticipates how the sage who will chronicle his adventures will describe this first one.

塞万提斯的作品向长篇小说自发性的发展过程的第二阶段是“记述者(们)”这个角色的发明。注意是复数形式,也就是塞万提斯故弄玄机,说本故事(吉诃德老爷的冒险)有“多位”记载者和传述者,这既增加了两个荒诞角色的真实性(credibility),也增加了小说形式的奇异性。小说的第一次冒险是由一个无名记述者(unnamed narrator)记载的,好像这个无足轻重。小说后面又会出现一些“不同记述者”对第一次突击的一些“事实”(factual matters)的不同看法。我们当然知道这些不同记述者其实都是塞万提斯了。插句题外话,我们从前面塞万提斯的小传知道《堂吉诃德》第二部隔了十多年才写完,在这期间,还真有不安分的某位西班牙文人续写了一本“《堂吉诃德》II”并且在塞万提斯的第二部出来之前就出版了,那个版本虽然实际上是剽窃,但却事实上的形成了不同的narrators的不同讲述,构成了一部小说之外的真实荒诞喜剧,这也是一种不可预测性和真实性的完美结合。Hardly has Don Quixote left home again when Cervantes thinks of ways in which those ideas about different narrators can be exploited for further fun: at a most inconvenient point he claims that this is where the written source material, and therefore the story itself, comes to a sudden end. The mysterious second author who is now introduced together with the lying Moorish historian Cide Hamete Benengeli and his hardly more reliable Morisco translator manage, between them, to sort the problem out, enable the story to continue and provide opportunities for playing literary games throughout the novel. All this is another parody of the romances of chivalry, which were often presented as Spanish translations of ancient documents.

在吉诃德老爷第二次冒险(应该就是风车冒险)的中途,塞万提斯决定更好的利用这个“多个记述者”的想法和写作技巧。他让原始记述者的记述嘎然而止,因此冒险故事也中止。然后塞万提斯造了一个神秘的第二记述者,这位作者和那位爱撒谎的摩尔人历史学者Cide Hamete以及他并不更加可靠的基督教归化者翻译师一起合作,把故事继续。使全书形成一个套中套/戏中戏的文学游戏。而这种写作手法其实也是对骑士浪漫文学的模仿,因为当时西班牙作者们在对古代文献进行西班牙语翻译的时候也会形成这样对古文本意见不一,翻译也截然不同的情况的出现。这个让我联想到了我们的国学。我们的国学在对上古五经(诗书礼易春秋)进行解读的时候,看起来都是用的汉字,但实际上是一种翻译。我们太把这些不同注者的观点当回事了,以为他们的讲述是真实的东西,比如朱熹那些人写的东西。我们不妨把朱熹写的东西看成一种对上古五经拙劣的翻译,把朱熹看成一位爱撒谎的徽州人历史学家和一个同样不可靠的徽州人儒教皈依者翻译师的合体罢了。It is at this point, the beginning of chapter IX, that Don Quixote is called a cuento for the second and last time. The story is wriggling out of the hands of Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra and into those of Cide Hamete Benengeli. Cervantes also marks this transition by informing us that the second part is beginning here, and by referring to ‘the great bulk of material that, as I imagined, was missing from this delectable tale’. ‘It seemed impossible and contrary to all good practice that such an excellent knight shouldn’t have had some sage who’d have made it his job to record his unprecedented deeds,’ Cervantes continues, as he perceives the potential of this cuento and includes the act of perceiving it as part of his story. Don Quixote’s growth from novella to novel can no longer be checked.

在第九章的开头,塞万提斯第二次也是最后一次把本书称为cuento(短篇故事)。小说正式从塞万提斯之手蠕动出来(wriggle out)落入到到那些众多记述者的手里面去了。塞万提斯进一步提示大家,说第一个冒险可能丢失了大量的历史记录(所以他才写得那么简单),说一个如此杰出的骑士一定会有某位智者(sage)以跟随他、记录他无与伦比的事迹为毕生职业。《堂吉诃德》一书的重要结构(桑丘,多位记述者)至此已引入搭建完成,再也没有什么能够阻挡它从短篇小说成长为长篇巨制了。原文实在太长,这个第一部分“Writing Don Quixote”我也分成上下两个部分吧。此为第一部分的上半部分。

主要讲了以下几点:

塞万提斯最初创作《堂吉诃德》的时候并没有想到写个长篇,他是按照短篇故事来构思的,但写着写着就刹不住车了。所以小说结构上并不谨严。《堂吉诃德》本来是对16世纪前70年流行的骑士浪漫文学的一个滑稽化模拟,以嘲讽骑士文学里面宣扬的那些不切实际的东西。但是这种嘲讽如此的滑稽搞笑,却更让大家记住了骑士文学。塞万提斯装模作样的给自己作品加上很多道德说教,但是却更好的嘲讽了道德说教。桑丘是很重要的角色。吉诃德和桑丘两人的长篇对话让角色发展,让小说也变得深刻。多个讲述人也是很重要的小说组成,也是非常现代的写作手法。对于脑子一根筋只知道标准答案一门心思要找到历史真相不允许抬杠的中国人来说实在太难理解了。 支付宝扫一扫

支付宝扫一扫 微信扫一扫

微信扫一扫